CENTRAL PARK THROUGH THE LENS

CENTRAL PARK THROUGH THE LENS: A SHARP LOOK AT AMERICAN SOCIETY

By the middle of the 19th century, New York had nearly quadrupled within 30 years and there was an urgent need for refuge from the overcrowding and noise of the developing city. In those days it was customary to connect to nature, to spend time and picnic in the cemeteries that were scattered throughout the city, and there was a bubble of silence and vegetation in the constant commotion. The architect of the Central Park is architect Frederick Lowe Olmsted – father of American landscape architecture. Among other things, he planned Niagara Falls Park, Prospect Park in Brooklyn and many other cities and universities in the US Yosemite National Park was created as a result of great pressure and push on his part, inspired by the construction of a public park in New York and other cities in the US Downing, who was visiting England, was deeply impressed by Birkhead Park, the world’s first public park opened in 1847. Downing was impressed by the fact that despite the sublime beauty of the park, there were children and women ‘whose owners were evidently working class.’ Thus was born the idea of building Central Park, All of which have access to it and the right to enjoy it, and not only the rich landowners who held private parks throughout the city. Today the last remaining private park in Manhattan is Gramercy Park – the concept that the land should be public and for everyone’s welfare, has become dominant. The park, which opened in 1858, is almost entirely planned on the basis of the rock mass in the center of Manhattan and prevented the continuation of the paving of Sixth and Seventh avenues. It has three artificial lakes, over 25,000 trees and 36 bridges decorated in a variety of building styles. When it was decided to turn the area into a park, there were about 1,600 people living in small villages and farms, mostly freed slaves and farmers of Irish and English descent. To this day, the park has an area called ‘Sheep Meadow’ in the park where sheep and cows graze. The park, which opened in 1858, is almost entirely planned on the basis of the rock mass in the center of Manhattan and prevented the continuation of the paving of Sixth and Seventh avenues. It has three artificial lakes, over 25,000 trees and 36 bridges decorated in a variety of building styles. When it was decided to turn the area into a park, there were about 1,600 people living in small villages and farms, mostly freed slaves and farmers of Irish and English descent. To this day, the park has an area called ‘Sheep Meadow’ in the park where sheep and cows graze. The park, which opened in 1858, is almost entirely planned on the basis of the rock mass in the center of Manhattan and prevented the continuation of the paving of Sixth and Seventh avenues. It has three artificial lakes, over 25,000 trees and 36 bridges decorated in a variety of building styles. When it was decided to turn the area into a park, there were about 1,600 people living in small villages and farms, mostly freed slaves and farmers of Irish and English descent. To this day, the park has an area called ‘Sheep Meadow’ in the park where sheep and cows graze.

The Sheep Brothers in Central Park. It was only in the 1930s that the sheep were evacuated and the park was designated exclusively for the leisure culture of New Yorkers

The park knew ups and downs, periods of flowering and periods of neglect and decline. One of the flowering periods of the park known as the events of the era was the 1960s and 1970s when social activism spilled into the park and large-scale demonstrations that took place were the beating pulse of American public opinion. Gatherings against the Vietnam War, the Black Panthers, the civil rights movement, the gay community demonstrations and rallies have become part of the park’s experience and attracted masses who felt it was the right place to be. This period attracted many photographers who saw the park as a microcosm of trends in the American street. These photographers were drawn to take pictures in Central Park and other parks scattered throughout the city, to decipher their secrets and to find in them the reflection of urban man. Central Park is a fascinating photographic space: Inspired by its religious faith and the Hudson Valley Painting School, which has found the landscape along the river the ‘Heaven on Earth’, Olsmedt planned the park to be an inspiration of transcendent beauty, Taste and quality that can educate those who reside in it to appreciate and consume culture and beauty. Within this harmony and the creation of architectural splendor, the photographers could find the urban man in the park to take a break from the crazy rhythm of the city and connect with nature and another internal rhythm. In the park you can see the sunbathers, the dog owners, the gymnasts and the runners, the yoga people and families with children, all coming to the park to find their little piece of God, to seclude themselves or look for a girlfriend. At night, parks in New York are closed and forbidden to enter, fearing that crime will find a place of activity and bring violence and danger. One of the most recognizable photographers with Central Park was Diane Arbus. Arbuz was a photographer of marginal cultures, exceptions and people who were not part of normative American society. It was found in the upper class, the poor, the rejected, and the communities in the periphery of the dominant culture of the 1960s. Within this harmony and the creation of architectural splendor, the photographers could find the urban man in the park to take a break from the crazy rhythm of the city and connect with nature and another internal rhythm. In the park you can see the sunbathers, the dog owners, the gymnasts and the runners, the yoga people and families with children, all coming to the park to find their little piece of God, to seclude themselves or look for a girlfriend. At night, parks in New York are closed and forbidden to enter, fearing that crime will find a place of activity and bring violence and danger. One of the most recognizable photographers with Central Park was Diane Arbus. Arbuz was a photographer of marginal cultures, exceptions and people who were not part of normative American society. It was found in the upper class, the poor, the rejected, and the communities in the periphery of the dominant culture of the 1960s. Within this harmony and the creation of architectural splendor, the photographers could find the urban man in the park to take a break from the crazy rhythm of the city and connect with nature and another internal rhythm. In the park you can see the sunbathers, the dog owners, the gymnasts and the runners, the yoga people and families with children, all coming to the park to find their little piece of God, to seclude themselves or look for a girlfriend. At night, parks in New York are closed and forbidden to enter, fearing that crime will find a place of activity and bring violence and danger. One of the most recognizable photographers with Central Park was Diane Arbus. Arbuz was a photographer of marginal cultures, exceptions and people who were not part of normative American society. It was found in the upper class, the poor, the rejected, and the communities in the periphery of the dominant culture of the 1960s. Everyone comes to the park to find their little piece of God, to be alone or to look for a girlfriend. At night, parks in New York are closed and forbidden to enter, fearing that crime will find a place of activity and bring violence and danger. One of the most recognizable photographers with Central Park was Diane Arbus. Arbuz was a photographer of marginal cultures, exceptions and people who were not part of normative American society. It was found in the upper class, the poor, the rejected, and the communities in the periphery of the dominant culture of the 1960s. Everyone comes to the park to find their little piece of God, to be alone or to look for a girlfriend. At night, parks in New York are closed and forbidden to enter, fearing that crime will find a place of activity and bring violence and danger. One of the most recognizable photographers with Central Park was Diane Arbus. Arbuz was a photographer of marginal cultures, exceptions and people who were not part of normative American society. It was found in the upper class, the poor, the rejected, and the communities in the periphery of the dominant culture of the 1960s.

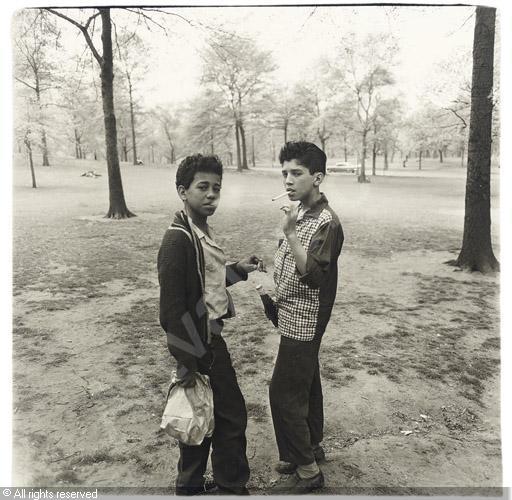

‘Two Boys Smoking in Central Park,’ by Diane Arbus

In the middle of the 20th century, Central Park was in the northern part of the Harlem Ghetto. From Harlem streets, Hispanic youth and African-American residents streamed into the park and shared the public space with their white neighbors, unprecedented in the United States, which until 1965 still had racial segregation laws. “I really believe there are things nobody would see if I didn’t photograph them”. In this statement, Diane Arbuz connects photography with a social purpose and floods the discussion of the “transparent” minorities that America left behind in the decade it was involved in the Vietnam War, the Cold War and the space race, and did not devote resources and attention to its internal problems, especially to minorities. Arbuz’s photography is in the category of social documentation, but in the 50s of the 20th century the perception of photography changed and the realization that there is no such thing as an accepted ‘photographic truth’ also opened the genre of documentary photography to subjective perspectives reflecting the photographer’s private truth, A personal position and not a representation of absolute truths. How do you photograph people closely? The fear of a hostile reaction is, of course, the main stumbling block. Arbuz developed a photographic approach full of compassion and empathy for her subjects. She did not look at their ‘others’ from a critical place, she did not look for the curiosity and did not find confirmation of her superiority through ‘inferior’ photographic subjects.

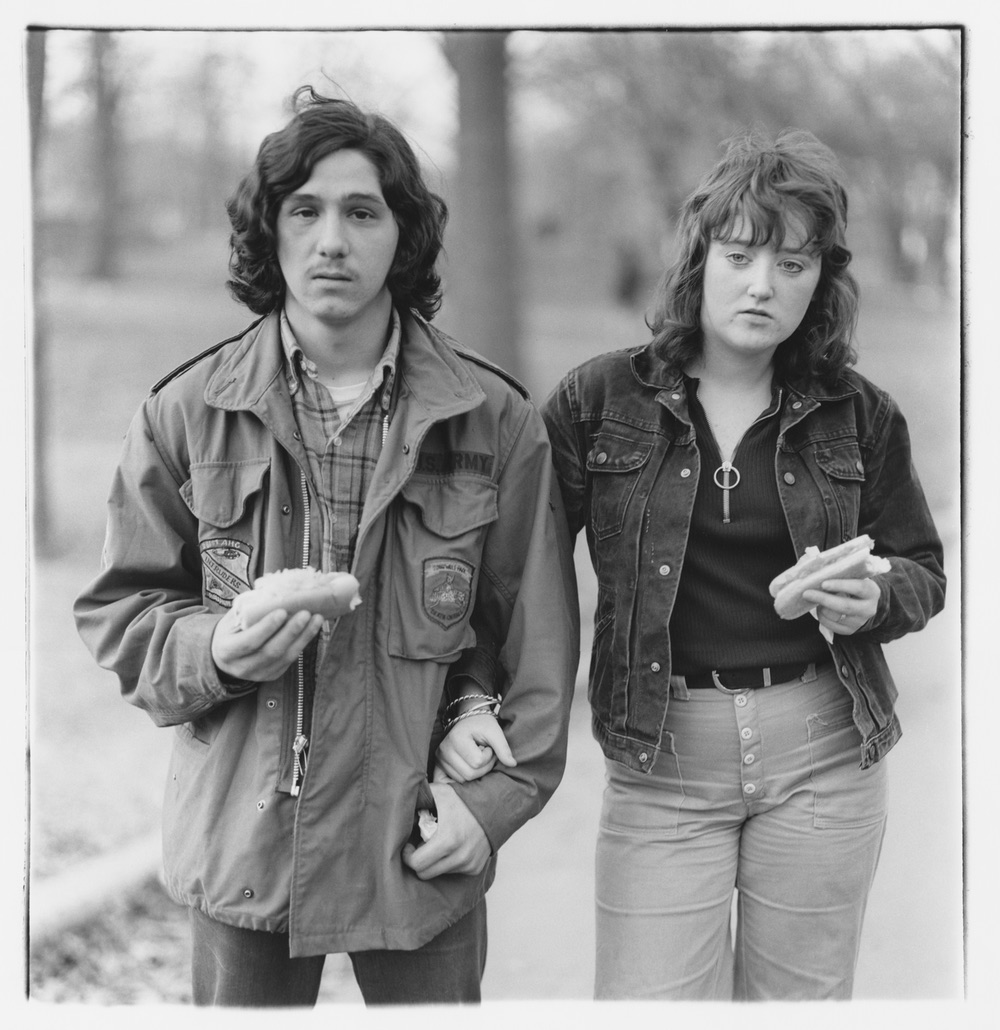

Arbus, A young man and his girlfriend with hot dogs in the park NYC, 1971

Arbuz did not “steal” photos or use telephoto lenses to shoot remotely, without the consent or knowledge of the subjects. She loved her subjects and they felt it. Her attention to them was a place of respect and appreciation for their war of survival. Each of them was her hero for a moment – in front of her camera stood transparent people in a rare moment of recognition and importance. What Diane Arbose was looking for? What does it cost? Arbose posed a question mark challenging our knowledge, the prejudices we approach people, how we catalog people instead of observing, communicating, and giving each encounter the chance to be unique and valuable. One of the prisms that Arbose looks at Park people is the humor that reveals another truth about the nature of people, the changing fashions and the extreme seriousness in which most of us look at ourselves and the world.

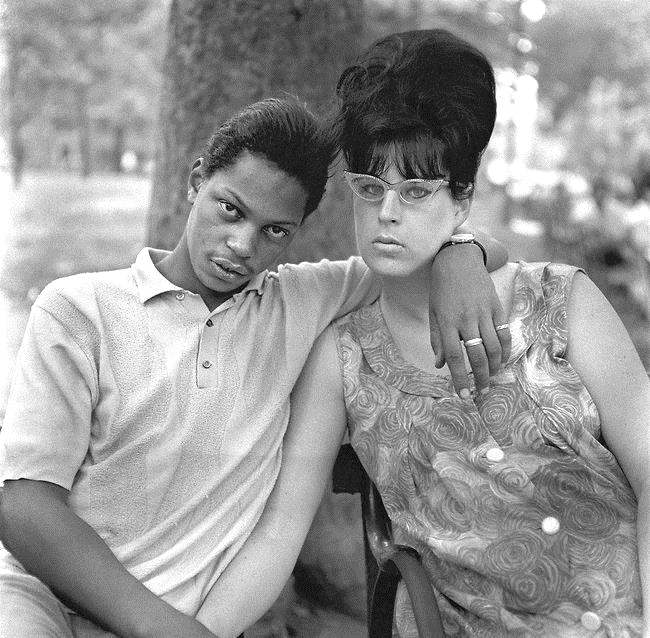

Arbus, A Young Man and His Pregnant Wife in Washington Square Park NYC, 1965

Todd Papajorg begins filming in Central Park about a decade after Diane Arbose, his work was called to book photographs: Passing Through Eden Papajorj views the park as a public territory claimed by many people at the same time. He photographs through an amused lens the attempts of the “territorial” people to mark their own space within the public sphere. His work exposes something essential to human nature – our need for protected territory, which we can mark with objects – a claim to short and limited territory.

The photographer examines how exposed space becomes private enough for people to be exposed – in their bodies, their intimacy with their spouses, their eating habits and other personal characteristics Which are usually reserved for the hidden space of the house. Thanks to Papajorg’s choice of a wide-angle lens rather than a telephoto lens, he receives not only the correct angle of vision but also makes his camera (and himself) at least threatening and the action of photography less penetrating. It always pays to focus on one phenomenon, a significant one, and watch it again and again.

Tod Papageorge, Central Park, New York, 1978

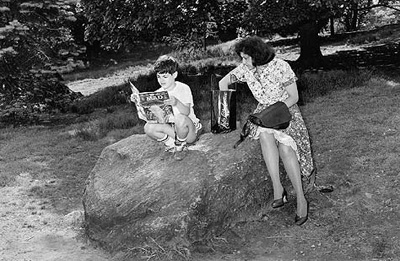

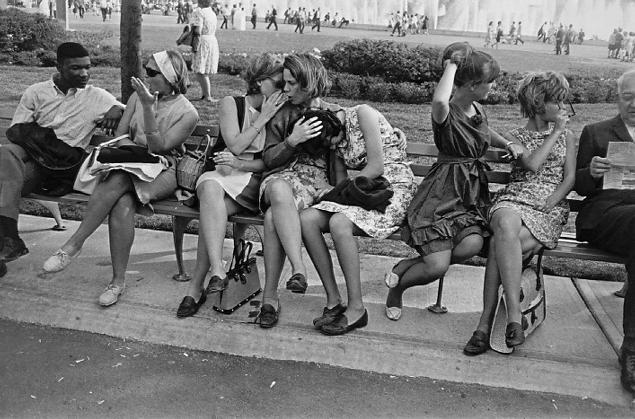

A lot of discoveries await us if we hold our gaze and study our subject over time. Papajor has been filming in Central Park, New York for over 25 years, during which he found a significant photographic object for him – benches: the public bench – that familiar piece of furniture that we do not hesitate to think about usually – has turned into a human behavior research laboratory. The bench is meant for sitting, he invites us to him by his very presence. But what the photograph deals with is not the obvious, but the way this space divides strangers, the exact distances that are subject to the social code of keeping the same distance from the people on either side of you. Body language also becomes a focus in his photographs.

Tod Papageorge, Central Park, New York

In the pictures before us, one can see the discomfort of one person who hides his face from the camera, the man and the woman who shut themselves up in their private world and disconnect from those around them through a newspaper they study.

Central Park, 1979 by Tod Papageorge

Papajorg is amused by the situations we are exposed to with our fears of the other. When strangers came to the same bench, Papajorj was there with his camera to bring a smile to the viewer, a smile that also has the pleasure of discovering ourselves in the picture and knowing how much it reflects us too.

Central Park, 1979 by Tod Papageorge

When he first started, Papajor met and connected with the man who became his close friend and mentor, the photographer Gary Winograd, one of the most important American photographers of the ’60s and ’70s. They used to meet and wander together in Central Park and photograph, discuss, and analyze their photographs together and learn from their differences in perception and perspective, especially from those situations where they filmed the same subject.

Tod Papageorge, Central Park Zoo, New York, 1967

This photograph taken on one of those days in the park was taken by Papajorg. The photographer relates that at the moment the couple passed by, his attention was focused on the fact that they were elegantly dressed and looked like two models. They led two chimpanzees dressed like children and locked in shoes. For him the subject was humorous and dealt with the ridicule and strangeness of New Yorkers. Next to him stood Gary Winograd and took this picture:

Garry Winograd, Central Park Zoo, New York, 1967

Winograd succeeded in filming the situation beyond the curiosity and succeeded in expressing the complexity of American society as a whole. The structure of this photograph is based on a classic model of family photography, the more thoughtful and serious looks of the man and woman, and the feeling of unease not found in Papajorg’s photograph sets the tone for this photograph. The picture reveals the exposed nerves of American society that in those years intermarriage were almost impossible and certainly unacceptable. America was torn by the tension between liberalism and progressive thinking, of which New York was its main incubator and the rest of America, which was almost entirely racist, sectoral, and characterized by tension, hostility and suspicion among whites and Afro-Americans in particular. The two monkeys’ adoration of the couple, just like children, adds another dimension to the picture and the children equation = future, posing another question mark about the direction that American society goes in those years. This comparison between the two photographs beautifully illustrates the role and location of the photographer: If at the beginning of his career, Photography is perceived as an objective medium that shows the truth through facts (photographed) that can not be doubted. In the middle of the 20th century, the photographer becomes a commentator on reality and does not describe it. The photograph is no longer a factual field but a subjective space, influenced by photographic decisions of frame, composition, context (and contextual output), point of view and of course the moment of photography.

Garry Winograd, 1965

A great example of this is the series of zoo photographs from the Schoenbrande Zoo in Central Park and the Bronx (New York). This witty series examines the relationship and communication between humans and animals, asks questions about humanity (of animals) and about us humans.

Garry Winograd, CENTRAL PARK ZOO 1967

The photographer floods these questions through a composition that usually does not focus on an esoteric occurrence, but offers a relatively wide space of occurrence in which there is more than one activity arena within the same frame.

The transition from documentation to personal interpretation is the most baffling leap the medium has made since its invention in 1839-40 until the middle of the twentieth century. Photography, with its appearance on the stage of history, freed art from the duty of realism and loyalty to reality, took on the role of documentation and enabled the emergence of modern art, but it also bound itself for its first 100 years to the same historical role of sweeping documentation and agreed upon everything: , Science, man, historical events and junctions as well as small situations from the lives of ordinary people – all have assumed their final form and their place as a private memory, collective and historical, in the archive embracing all of the photographic inventory. In light of this, the importance of the transition from documentation to interpretation and neglect of the perception that there is an agreed upon and objective reality that the camera can reflect is enormous and in light that the photographer today in the parks or in the street can find a personal point of view as a photographer. And we’ll take the photo in Central Park … Another bench, that of Winograd: Unlike the photographed benches of Arbose and Pappage.

Garry Winograd, World’s Fair, 1964

Eyal Perry is an artist, a senior lecturer in photography and a leader of workshops and art tours in New York

Cover photo: Robert Frank, next of July-Jay, New York, 1954